One of the defining paradoxes of the 21st century is the concurrent acceleration of two opposing forces. On one hand, our technological prowess constructs an ever-more sophisticated buffer between our daily lives and the raw processes and forces of the natural world. Our food is packaged, our climates are controlled, and our social interactions are increasingly mediated by digital interfaces.

Yet, on the other hand, an ever conscious and urgent awareness of our absolute dependence on that same natural world has permeated the global consciousness. The tangible realities of ecological instability, from atmospheric carbon concentrations to critical biodiversity loss, have dismantled the illusion that humanity operates in a sphere separate from its planetary host. This forces a critical re-examination of our fundamental relationship with nature, for the attitude we hold, such as one of reverence, dominion, or partnership, directly informs the future we architect.

The contemporary mindset is not a monolith; it is a complex sociological stratum, with each layer representing a distinct era of philosophical, economic, and religious thought. To navigate the immense challenges of our time, one must first become a cartographer of this internal landscape, tracing the long and often contradictory evolution of human attitudes towards the living world.

Table of Contents

Phase 1: Primordial Connection – Nature as Animate and Sacred

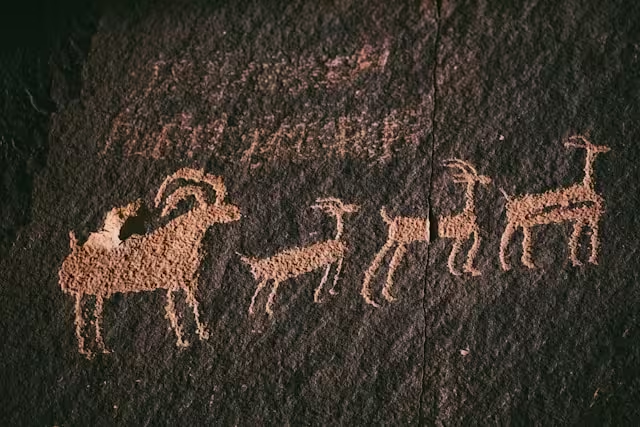

To comprehend the origin point of the human-nature relationship, one must strip away modern constructs and access a worldview that is fundamentally different from our own. For early Homo sapiens and our hominid ancestors, survival was not an abstract concept but a direct, daily negotiation with the forces and inhabitants of the surrounding ecosystem. This constant, high-stakes interaction fostered a perspective that modern scholarship has labeled animism.

The Animistic Worldview

Animism is not a religion in the institutional sense but a fundamental mode of perception. In this framework, the rigid line between subject and object, so central to modern thought, is porous or nonexistent. A river was not merely a body of water; it possessed a spirit, agency, and temperament. A mountain was not just a geological formation; it was a powerful being. Animals were not mindless beasts; they were kin, ancestors, or rival nations with their own societies and intelligence. This perspective posits a world populated not by “its,” but by a vast community of “thous.”

This was not a product of primitive superstition but a highly functional cognitive strategy. Attributing agency to the non-human world—assuming that a rustle in the grass is a predator until proven otherwise—is a survival-positive trait. But it goes deeper than simple threat assessment. It creates a framework for a reciprocal relationship. If the forest is a living entity, one does not simply take from it; one asks permission, performs rituals of gratitude, and understands that actions have reactions. The world is a web of social relationships that extends beyond the human species, and our place within it is that of one member among many, not the master of the system.

Ecological Function: A Relationship of Reciprocity and Fear

Within this animistic context, the human attitude was a sophisticated blend of intimate familiarity and profound respect, often manifesting as a healthy fear. Fear was not a negative emotion to be conquered but a vital signal of respect for power. One feared the storm, the predator, and the river in flood because they held the real and immediate power of life and death. This fear ensured caution and prevented the kind of hubris that would lead to catastrophic misjudgment.

Consequently, human action was governed by a principle of reciprocity. A successful hunt was followed by rituals honoring the spirit of the animal. Foraging for medicinal plants involved specific protocols to ensure the continued vitality of the population. This was not a conservation ethic in the modern sense; it was an inherent understanding of interdependence. Humans were an integrated, non-dominant part of their ecosystem, and their cosmology directly reflected this ecological reality. The world was sacred precisely because it was alive, and survival depended on navigating the intricate social and spiritual currents of that living system.

Phase 2: The Great Divergence – Agriculture and Anthropocentrism

The transition from nomadic foraging to sedentary agriculture, beginning roughly 12,000 years ago, represents arguably the most significant rupture in the history of the human-nature relationship. This Neolithic or Agricultural Revolution did not just change how humans acquired food; it fundamentally re-engineered their psychology, social structures, and perception of the world, creating a great divergence from the animistic past.

The Agricultural Revolution’s Impact

The act of cultivation created, for the first time, a sharp and defensible boundary between the human domain and everything else. The cultivated field, the irrigation ditch, and the granary represented order, predictability, and human ingenuity. This space was “civilization.” Beyond the fence or the stone wall lay the forest, the swamp, and the mountain—the “wilderness.” This untamed space was no longer just a provider and co-habitant; it became a source of threats—predators that stole livestock, weeds that choked crops, and droughts that nullified labor.

This physical boundary created a corresponding psychological one. Nature was transformed from an all-encompassing system of which we were a part into an external “other” that had to be controlled, managed, and defended against. The primary human project shifted from adapting to the rhythms of the ecosystem to imposing human will upon it. Success was measured not by the subtlety of one’s integration but by the scale of one’s transformation of the landscape.

The Philosophical Codification of Human Supremacy

As civilizations grew in complexity, their foundational myths and philosophies evolved to reflect and justify this new, dominant posture. In the West, this manifested as anthropocentrism—the worldview that places humanity at the center of existence. Greek philosopher Aristotle, in his Politics, outlined a natural hierarchy wherein “plants exist for the sake of animals and animals for the sake of man.” This intellectual framework provided a powerful rationale for the instrumental use of nature. The non-human world had no intrinsic value; its purpose was to serve human ends.

This perspective was amplified and codified by dominant interpretations of Judeo-Christian theology. The directive in the Book of Genesis to “have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” was widely interpreted not as a call for responsible stewardship, but as a divine license for exploitation.

This view of nature solidified a hierarchical Great Chain of Being, with God at the top, followed by angels, humanity, animals, and plants. In this structure, the flow of value and purpose was strictly top-down. Nature was no longer a sacred community of kin but a collection of resources provided by a transcendent God for the exclusive use of his chosen creation, humanity.

Phase 3: The Mechanization of Nature – The Scientific & Industrial Revolutions

If agriculture created the initial separation from nature, the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions hammered a permanent wedge into that divide. This period, spanning roughly from the 17th to the 19th centuries, systematically de-sacralized the natural world, reframing it as an inanimate machine to be understood, disassembled, and re-purposed for human progress.

The Enlightenment and the Clockwork Universe

The philosophical engine of this shift was the Enlightenment, particularly the dualism promoted by René Descartes, who famously separated the thinking mind (res cogitans) from the material world (res extensa). In this view, only humans possessed minds and souls; the rest of the universe, including all animals and plants, was simply unthinking matter, operating on purely mechanical principles.

This led to the powerful metaphor of the “clockwork universe.” Nature was seen as a vast, intricate machine, created by a divine watchmaker (God), but now running on its own predictable, mathematical laws. The human mission, as articulated by thinkers like Francis Bacon, was to uncover these laws through science in order to gain “dominion over creation” and use it to relieve man’s estate.

This perspective stripped nature of its last vestiges of agency and spirit. It was no longer a living system to be respected but a complex problem to be solved and a resource to be mastered. An animal’s cry of pain was not a sign of suffering but the mechanical squeak of a machine, no different from a gear grinding.

Nature as Raw Material

The Industrial Revolution was the practical application of this mechanistic worldview on a global scale. The steam engine, the factory, and the mine were physical testaments to humanity’s power to bend the natural world to its will. Nature’s value was reduced to its economic potential. A forest was not an ecosystem; it was a quantity of board-feet of timber. A mountain was not a sacred peak; it was a repository of coal and iron ore. A river was not a lifeblood; it was a source of hydromechanical power and a convenient conduit for industrial waste.

This attitude is perfectly illustrated by the history of Titusville, Pennsylvania, the very birthplace of the American oil industry. Here, the ancient, stored sunlight of the Carboniferous period was not seen as a sacred inheritance but as “black gold,” a raw material to be extracted with maximum speed and efficiency to fuel the engines of progress. The landscape was irrevocably altered, polluted, and transformed into a site of production. This was the ultimate expression of the mechanistic ethos: nature as a standing-reserve, a warehouse of parts for the great human industrial project.

Phase 4: The Counter-Current – Romanticism and Transcendentalism

Human psychology abhors a vacuum. The relentless drive of industrialization and the cold rationalism of the Enlightenment created a spiritual and emotional void that a powerful counter-movement rose to fill. Beginning in the late 18th century, the Romantic and Transcendentalist movements represented a profound recalibration, seeking to re-enchant the world that science had mechanized.

The Romantic Rebuke

Romanticism, championed in Europe by figures like philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and poet William Wordsworth, was a direct and passionate rebellion against the “dark Satanic Mills” of industry. It rejected the idea of nature as an inert machine and instead elevated it to the status of a living, divine force. For the Romantics, civilization was corrupt, artificial, and debasing, while nature was the source of authenticity, moral purity, and intense emotion.

They cultivated an appreciation for The Sublime—the feeling of awe, terror, and wonder experienced in the face of nature’s overwhelming power, such as a violent storm, a towering mountain range, or a vast ocean. This was a direct refutation of the desire for control; the point was to be humbled and emotionally overwhelmed by a power far greater than oneself. Nature was no longer an object for analysis but a subject for profound emotional and spiritual communion.

American Transcendentalism

This European sentiment found fertile ground in North America, where it evolved into Transcendentalism. Led by thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and his protégé Henry David Thoreau, this movement sought a more direct, personal, and intellectual engagement with nature. Emerson’s concept of the “Oversoul” posited that every individual soul was part of a larger divine consciousness that was also present in nature. Therefore, to understand oneself, one must commune with the natural world.

Thoreau put this philosophy into practice. His two years at Walden Pond, chronicled in his masterwork Walden, was a deliberate experiment in “living deep and sucking out all the marrow of life.” It was a protest against the mindless consumerism and conformity of industrial society. For Thoreau, a walk in the woods was not mere recreation; it was a moral and intellectual necessity. He famously wrote, “in Wildness is the preservation of the World,” a statement that directly inverted the centuries-old belief that civilization must be preserved from the wild. Together, the Romantics and Transcendentalists re-infused nature with intrinsic value, setting the philosophical stage for the conservation and environmental movements to come.

Phase 5: The Managerial Shift – Conservation vs. Preservation

By the late 19th century, the consequences of the industrial worldview were becoming impossible to ignore. Vast forests had been clear-cut, species like the passenger pigeon were hunted to extinction, and watersheds were fouled. In response, a new, more pragmatic attitude emerged, primarily in the United States, giving birth to a formal conservation movement. This movement, however, was immediately split by a foundational ideological conflict: the battle between conservation and preservation.

The Birth of the Conservation Movement

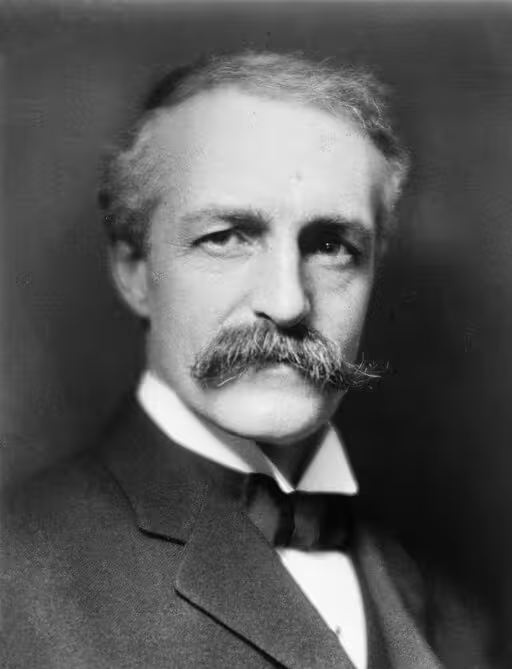

The dominant wing of this new movement was utilitarian conservation, led by Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the U.S. Forest Service. A pragmatist and a scientist, Pinchot was no Romantic. He inherited the view of nature as a collection of resources, but with a crucial modification. He argued that these resources must be managed scientifically and sustainably for long-term human benefit. His guiding principle was “the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest time.”

This was not a call to leave nature alone, but to manage it efficiently. The goal of forestry, in his view, was not to preserve old-growth forests but to produce a perpetual supply of timber. This “wise use” philosophy treated nature like a well-managed business, with resources as its capital. It was a significant step beyond outright exploitation, but it remained firmly anthropocentric. The value of nature was still defined entirely by its utility to humans.

The Preservationist Ethic

In stark opposition to Pinchot stood John Muir, a Scottish immigrant, inventor, and wilderness evangelist who became the spiritual father of the preservation movement and the founder of the Sierra Club. Having walked from the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico and found his church in the grandeur of California’s Sierra Nevada, Muir was a direct heir to the Transcendentalists. For him, nature was not a collection of resources; it was a temple, sacred and divine in its own right.

Muir argued passionately for the intrinsic value of wilderness. He believed that ancient forests, wild rivers, and granite peaks had a right to exist for their own sake, independent of any use to humanity. He advocated for the complete preservation of these areas from all forms of economic development.

This ideological clash came to a head in the famous battle over Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yellowstone National Park, which Pinchot supported damming to provide water for San Francisco, and which Muir fought desperately to save, calling its destruction a form of sacrilege. Though Muir lost that battle, his preservationist ethic laid the groundwork for the modern environmental movement and the idea that some places should be protected not for what they provide, but simply for what they are.

Phase 6: The Ecological Awakening – A Systems Perspective

The first half of the 20th century was largely dominated by the Pinchot-style conservation ethic. The second half, however, witnessed another profound shift in consciousness, moving beyond the debate over resource management to a more holistic, systemic understanding of the natural world. This was the ecological awakening.

The Land Ethic

The intellectual bridge to this new perspective was built by Aldo Leopold, a forester initially trained in the Pinchot school of thought. Through a lifetime of observation, chronicled in his posthumously published classic, A Sand County Almanac (1949), Leopold underwent a profound conversion. He came to see nature not as a collection of independent resources but as a single, complex, interconnected community—an ecosystem.

From this insight, he developed his revolutionary “Land Ethic.” Leopold argued that humanity’s ethical frameworks had evolved over time—from relations between individuals to relations with society—and that the next logical step was to extend ethical consideration to “the land,” which he defined as the entire community of soils, waters, plants, and animals.

The Land Ethic, he wrote, “changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it.” This was a direct assault on anthropocentrism. Under this ethic, an action is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community, and wrong when it tends otherwise. It provided a new philosophical foundation for environmentalism, grounded in the science of ecology.

The Environmental Movement

If Leopold provided the philosophy, biologist Rachel Carson provided the catalyst that sparked a global movement. Her meticulously researched and powerfully written book, Silent Spring (1962), exposed the devastating and far-reaching effects of synthetic pesticides like DDT. Its impact was seismic because it demonstrated the core tenets of ecology to the public in a terrifyingly personal way.

Carson showed how a poison sprayed on fields could travel through the food web, accumulating in the bodies of birds and fish, and ultimately, humans. She revealed a world of invisible connections where an action in one place could have devastating consequences far away in both distance and time. Silent Spring made ecology a household word and shifted the focus of concern from visible scars on the landscape (like clear-cuts) to invisible, systemic threats like chemical pollution and radiation.

This new awareness, centered on environmental quality and public health, mobilized a new generation of activists, leading directly to the first Earth Day in 1970 and the passage of landmark environmental legislation. The modern environmental movement was born, armed with Leopold’s ethic and galvanized by Carson’s revelations.

Phase 7: The Contemporary Synthesis – Crisis, Biophilia, and Cultural Re-evaluation

As of 2025, we stand at another critical inflection point. The disparate threads of our long and tangled relationship with nature are converging, forced together by the realities of a global crisis and illuminated by new scientific insights. Our contemporary attitude is a complex synthesis of all that has come before, struggling to find a stable form.

The Anthropocene and the End of “Away”

Geologists have termed our current epoch The Anthropocene, signifying that human activity has become the dominant geological force on the planet. Climate change, mass extinction, ocean acidification, and the global prevalence of microplastics have demonstrated a final, unassailable truth: there is no “away.” The industrial era’s convenient fiction of throwing waste “away” has collapsed. The planet is a closed system, and the consequences of our actions are not external but are returning to us as feedback loops that threaten the stability of the very civilization they were meant to support. This reality is forcing a pragmatic, survival-based re-evaluation of our relationship with the biosphere, moving beyond ethics to a matter of existential necessity.

The Biophilia Hypothesis

Concurrent with this crisis, a scientific hypothesis has emerged that validates the intuitions of the Romantics and Transcendentalists. In 1984, the renowned biologist E.O. Wilson proposed the Biophilia Hypothesis, which suggests that humans have an innate, genetically encoded tendency to affiliate with other forms of life. He argued that for hundreds of thousands of years, our survival and well-being depended on a deep, nuanced attention to the natural world.

This long evolutionary history has left us with a biological need for nature; its presence can lower stress, improve cognitive function, and enhance healing, while its absence can create a kind of psychological malady. This provides a scientific, biological argument for nature preservation, rooted not just in ecological stability or ethics, but in our own mental and physical health.

Cultural Pluralism

Finally, the contemporary era is marked by a growing and long-overdue humility. The Western trajectory of dominion and exploitation is increasingly recognized not as the universal human story, but as one specific, culturally-contingent path. There is an increasing interest in and respect for other worldviews, particularly Indigenous Ecological Knowledge (IEK).

Many indigenous cultures around the world never experienced the agricultural or industrial ruptures in the same way and have maintained a worldview closer to the original animistic paradigm; one based on kinship, reciprocity, and seeing the land as a community of relatives rather than a collection of resources. This cultural pluralism offers alternative models for a sustainable human-nature relationship, providing valuable wisdom for a world searching for a new path.

Conclusion: Towards a Regenerative Paradigm

The evolution of human attitudes towards nature is a dramatic, millennia-long narrative of unity, separation, domination, and the slow, arduous journey back towards reintegration. We have journeyed from being a fearful child of the living world to a rebellious adolescent, convinced of our own supremacy, and now to a chastened adult, beginning to understand the profound consequences of our actions. The mechanistic worldview that built the modern world is insufficient to sustain it.

The critical challenge of the 21st century is to consciously forge a new, durable paradigm. This future attitude cannot be a simple return to a pre-scientific past, nor can it continue the hubris of the industrial age. It must be a sophisticated synthesis: one that embraces the scientific rigor of ecology as articulated by Leopold and Carson; that accepts the ethical responsibility of being a citizen, not a conqueror, of the biotic community; and that honors the deep, innate psychological and biological need for connection with the living world, a need now given voice by the Biophilia hypothesis.

The future of our species depends not on our ability to further control nature, but on our wisdom in learning to once again integrate with it.