Have you ever wondered how you can walk through a dense forest without constantly bumping into trees? Or how you can navigate a complex website, intuitively knowing what to click and where to go next? The answer is not magic; it is a remarkable and instantaneous process happening within your brain.

This process relies on a constant stream of visual information from the world around you. Your brain acts like a supercomputer, piecing together clues to build a live, three dimensional map of your surroundings. This incredible ability is known as spatial awareness. It is our cognitive skill to understand our body’s position in relation to the objects and spaces around us. Without strong spatial awareness, even simple tasks like catching a ball or parking a car would become nearly impossible.

This article will deconstruct the fundamental visual cues your brain uses to create this rich understanding. We will explore how these timeless principles of perception are not just for psychologists to study, but are essential tools for anyone who designs our world, from architects shaping our cities to developers crafting our digital experiences. Understanding these cues is the key to creating environments, both real and virtual, that feel intuitive, comfortable, and easy to navigate.

Table of Contents

The Foundational Pillars: What Are Visual Cues?

At its core, a visual cue is any piece of information from the environment that our eyes capture to help us understand space, distance, and depth. Think of these cues as data points. When you use a GPS, it gathers data from multiple satellites to pinpoint your exact location. Your brain does something similar, but instead of satellites, it uses visual cues from the world to build a rich and accurate model of where you are.

This process is absolutely essential for our spatial awareness. Without these constant signals, the world would appear as a flat, confusing jumble of shapes and colors. We would have no sense of what is near, what is far, what is large, or what is small.

Scientists and artists have studied these cues for centuries, and they can be sorted into two primary categories. The first is Monocular Cues, which are clues about distance and depth that you can perceive with just one eye. The second is Binocular Cues, which require both of your eyes working together to provide a true sense of three dimensional depth. Together, these two sets of cues provide the foundation for our entire visual understanding of the world and form the bedrock of our spatial awareness.

Monocular Cues: Perceiving the World in 2D

Monocular cues are the workhorses of our visual system. They are so powerful that they allow us to perceive depth in flat images like photographs, paintings, and, most importantly for modern life, on screens. For anyone designing a website, app, or digital graphic, understanding these cues is not just helpful; it is a requirement for creating effective and user friendly experiences. Because they only require one eye, these are the exact same cues that artists throughout history, especially during the Renaissance, mastered to create realistic depth on a flat canvas. Let’s break down the most important monocular cues that contribute to our spatial awareness.

Linear Perspective

Linear perspective is the observation that parallel lines, like the sides of a straight road or railroad tracks, appear to get closer and closer together until they meet at a single point in the distance. This meeting point is called the vanishing point. Your brain automatically interprets this convergence of lines as a powerful signal of depth. A road that narrows sharply is understood as one that stretches far into the distance.

- Design Application: In web design, artists can use images with strong linear perspective for background headers to create an immediate sense of depth and scale. This can make a two dimensional screen feel more like a window into a larger world, drawing the user into the experience. This manipulation enhances the user’s digital spatial awareness.

Relative Size

This is one of the most simple and effective visual cues. If you see two objects that you know are roughly the same size, the one that takes up more space in your field of vision (the one that looks larger) is perceived as being closer to you. A person standing twenty feet away will appear much larger than a person standing a hundred feet away. Your brain uses this difference in apparent size to calculate distance and build its model of the world, a key function of spatial awareness.

- Design Application: This principle is the foundation of visual hierarchy in design. On a webpage, the most important element, like a main headline or a “Buy Now” button, is often made larger than the surrounding elements. This not only draws the user’s eye but also makes the element feel closer and more significant, guiding their interaction with the page.

Occlusion (or Interposition)

Occlusion happens when one object partially blocks the view of another object. Your brain instantly and correctly assumes that the object doing the blocking is closer than the object being blocked. If you see a tree in front of a house, you know without a doubt that the tree is closer to you. This cue is so powerful that it can override other cues. It is a fundamental building block of how we develop spatial awareness from a very young age.

- Design Application: This is used constantly in modern User Interface (UI) design. Think about a pop up window, a notification, or a dropdown menu. These elements appear on top of the main content, partially occluding it. Designers often add a subtle drop shadow to the overlapping element to enhance this effect, making it feel more tangible and clearly positioned in front of the background.

Texture Gradient

Look at a cobblestone street or a field of grass. The texture of the ground closest to you is sharp, clear, and detailed. You can see individual stones or blades of grass. As you look farther into the distance, that texture becomes finer, less detailed, and seems to blend together. This change is called the texture gradient. A smooth texture gradient is a strong signal to your brain that a surface is stretching away from you, providing critical information for spatial awareness.

- Design Application: In digital design, especially in video games or virtual environments, artists use texture gradients to make surfaces look realistic and vast. A detailed, high resolution texture is used for the foreground, which then fades into a less detailed, blurred texture for the background, saving processing power while creating a convincing illusion of depth.

Aerial Perspective (or Relative Clarity)

On a clear day, look toward distant mountains or buildings. You will notice they appear hazier, less distinct, and often have a bluish tint compared to objects that are close to you. This is called aerial perspective. It happens because we are looking through more of the Earth’s atmosphere, which is filled with tiny particles of dust and water vapor that scatter light. Your brain learns to interpret this haziness as a sign of great distance, another tool it uses to refine your spatial awareness.

- Design Application: Web designers use this principle to create focus. They might make background images or less important elements slightly faded, desaturated, or blurred. This pushes them into the background visually and makes the crisp, clear foreground elements, like text and buttons, pop out and command the user’s attention.

Motion Parallax

This is the only monocular cue that requires movement. As you are moving (for example, looking out the side window of a moving car), objects that are close to you, like fence posts or road signs, seem to fly by very quickly. Objects farther away, like trees on a distant hill or clouds in the sky, appear to move much more slowly or not at all. Your brain measures the difference in the apparent speed of these objects to calculate their relative distance, giving you a dynamic sense of spatial awareness.

- Design Application: This effect is famously used in web design as “parallax scrolling.” As a user scrolls down a page, the background image moves at a slower rate than the foreground content.12 This creates a visually engaging and immersive 3D effect that can make a simple website feel more dynamic and spatially complex.

Light and Shadow

The way light falls on an object and the shadows it casts provide a huge amount of information about that object’s shape, form, and position in space. Shadows can tell us if an object is on the ground or floating, if its surface is smooth or rough, and where it is in relation to other objects. Our brains are expertly tuned to interpret these patterns of light and dark to understand the three dimensional nature of the world, a process vital to our spatial awareness.

- Design Application: The use of light and shadow is central to design philosophies like Google’s Material Design. Buttons and other interactive elements are given subtle shadows to make them look like they are slightly raised above the background. This makes them appear tangible and signals to the user that they can be pressed. This simple trick greatly improves a website’s usability.

Binocular Cues: The Advantage of True 3D Vision

While monocular cues are powerful, they are ultimately tricks the brain uses to guess at depth. Binocular cues, which require both eyes, provide a much more direct and accurate measurement of the three dimensional world. This is where we get our true sense of depth perception, which elevates our spatial awareness to a much higher level. There are two main binocular cues.

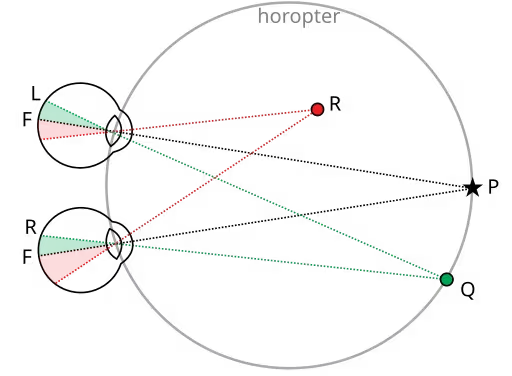

Stereopsis (Retinal Disparity)

Because your eyes are set a few inches apart, each one captures a slightly different image of the world. This difference between the two images is called retinal disparity. You can see this for yourself. Hold a finger up about a foot in front of your face. Close your left eye and look at it with your right. Now switch, closing your right eye and looking with your left. Notice how your finger appears to jump back and forth in relation to the background. Your brain takes these two slightly different images and fuses them into one single, seamless picture.

The process of fusing these images is what creates the powerful sensation of 3D depth, an effect known as stereopsis. This is the most potent depth cue we have, and it is what allows us to perform precise tasks like threading a needle or catching a fast moving object. It is the core of our advanced spatial awareness.

- Technical Context: This is precisely how 3D movies and Virtual Reality (VR) headsets work. A 3D movie presents a slightly different image to each of your eyes using special glasses. A VR headset has two small, separate screens, one for each eye, that do the same thing. By hijacking this natural process, these technologies can create an incredibly convincing illusion of being in a three dimensional space.

Convergence

When you look at an object, your eyes have to pivot inward to focus on it. This inward turning of the eyes is called convergence. If you are looking at something far away, your eyes are pointed nearly straight ahead. As the object gets closer to your face, your eyes must turn inward more and more to keep it in focus. Your brain receives feedback from the tiny muscles that control your eye movements.

It uses the amount of tension in these muscles to help calculate how far away the object is. More tension means the object is closer. While it is most effective for objects within about arm’s length, it provides yet another layer of data that contributes to our overall spatial awareness.

The Neurological Engine: How the Brain Processes Spatial Information

Understanding these visual cues is only half the story. The truly brilliant part is how our brain processes this flood of information to build our sense of spatial awareness. This complex task is not handled by one single part of the brain but by a network of specialized regions working together. A user’s spatial awareness is a product of this incredible biological computation.

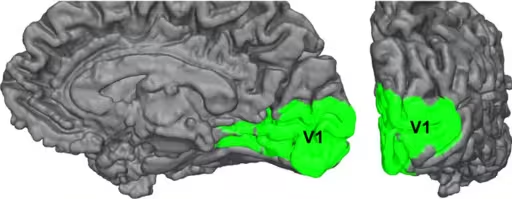

The process begins in the back of your brain in the Visual Cortex, which is located in the occipital lobe. This area acts like the initial processing plant for all the raw data coming from your eyes. It detects basic features like lines, edges, colors, and motion. But this is just the first step. The visual cortex does not understand what it is seeing; it just processes the patterns.

From there, the information is sent along different pathways to other brain regions. For our sense of spatial awareness, one of the most important destinations is the Parietal Lobe, located near the top and back of the head.

The parietal lobe is the brain’s integration center. It takes the visual data and combines it with other sensory information, such as your sense of touch and your body’s position (a sense called proprioception). It is in the parietal lobe that the brain constructs the coherent, three dimensional map of the world that we experience. It answers the critical questions: “Where am I?” and “Where are things in relation to me?” Damage to this area of the brain can severely disrupt a person’s spatial awareness, making it difficult for them to navigate even familiar places.

One of the most famous demonstrations of this innate ability is the “Visual Cliff” experiment, conducted by psychologists Eleanor J. Gibson and Richard D. Walk in the 1960s. They placed infants on a table that was half solid and half a thick sheet of glass. Under the glass, the floor dropped away, creating the illusion of a cliff. Even infants who were too young to have had any experience with falling would overwhelmingly refuse to crawl out over the “deep” side. This suggested that the ability to perceive depth, a cornerstone of spatial awareness, is at least partly hardwired into our brains from birth.

Applications in Design: Crafting Intuitive Spaces

A deep understanding of these visual principles is not just an academic exercise. It is a practical toolkit for anyone who creates the environments we live, work, and play in. The most successful designs, whether for a physical building or a digital app, are the ones that speak the brain’s native language of space. When designers leverage these cues effectively, they create experiences that feel natural, intuitive, and effortless to use, enhancing our spatial awareness within those contexts.

Biophilic and Architectural Design

Architects are masters of manipulating spatial awareness. They use cues like linear perspective with long hallways or rows of columns to make a space feel grand and expansive. They use light and shadow, with strategically placed windows and skylights, to sculpt a room and guide people through it. They use occlusion by placing walls and partitions to create separate zones or to hide and reveal views as you move through a building, creating a sense of discovery.

Good biophilic design, which seeks to connect people with nature, often uses these principles to create views that have multiple layers of depth (a nearby plant, a middle ground garden, and a distant view of the sky) to create a restorative and visually engaging environment.

Web & UI/UX Design

In the digital world, the screen is flat, but the user’s experience does not have to be. User Experience (UX) designers are essentially architects of digital space. They use visual hierarchy (making important things bigger and crisper) to guide a user’s attention. They use occlusion and shadows to manage the Z axis (the imaginary dimension of depth on a screen), making it clear which elements are on top and interactive. This careful management of digital space is critical for good spatial awareness on a website. Without it, a user can quickly feel lost and confused.

The goal is to create affordances, which are design cues that signal how an object can be used. A button with a shadow affords clicking. By using these cues, designers build a mental model for the user, making the interface feel less like a flat page and more like a tangible, navigable space.

Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR)

For developers of VR and AR, accurately recreating visual cues is the most important task. If there is a mismatch between what the user’s eyes see and what their body feels, it can quickly lead to motion sickness and a poor experience. VR developers must perfectly replicate motion parallax, stereopsis, and linear perspective to create a believable sense of presence. A successful VR experience is one where the user’s spatial awareness is completely convinced that the virtual world is real. Getting these details right is the difference between a breathtaking simulation and a nauseating one.

Can Spatial Awareness Be Improved?

The good news is that spatial awareness is not a fixed trait. Like any skill, it can be sharpened and improved with practice. If you feel that your sense of direction or your ability to visualize objects in 3D could be better, there are many activities you can do to train your brain. An enhanced spatial awareness can have benefits in many areas of life, from driving and sports to design and problem solving.

Mental and Physical Exercises

- Puzzles and Games: Activities like jigsaw puzzles, 3D modeling software, and games like Tetris or Minecraft are excellent workouts for your brain’s spatial processing centers. They force you to mentally rotate objects and understand how different parts fit together.

- Map Reading: In an age of GPS, the skill of reading a physical map is fading, but it is one of the best ways to improve your spatial awareness. It forces you to connect a two dimensional representation (the map) with the three dimensional world around you.

- Sports: Many sports are fantastic for developing spatial awareness. Sports like basketball, tennis, or soccer require you to constantly track the position of a ball, other players, and yourself, all in a fast moving, dynamic environment.

Mindful Observation

One of the simplest ways to improve your spatial awareness is to simply pay more attention to the world around you. The next time you are outside, consciously look for the visual cues we have discussed.

- Notice the texture gradient of the leaves on a tree or the bricks on a wall.

- Pay attention to the effects of aerial perspective on distant hills.

- Observe how shadows change throughout the day and how they define the shape of objects.

- When you are a passenger in a car, focus on the motion parallax effect.

By actively noticing these details instead of just passively seeing them, you are training your brain to become more sensitive to the rich spatial information that is always available. This mindful practice can make the world seem more vibrant and detailed, while simultaneously strengthening your innate spatial awareness.

Conclusion: The Unseen Language of Space

Our ability to perceive and navigate the world is a silent miracle that we perform every waking moment. It is built on a set of universal visual cues, from the simple logic of occlusion to the complex neuroscience of stereopsis. These principles work together seamlessly, allowing our brains to construct the rich, three dimensional reality we experience. A strong spatial awareness is fundamental to our interaction with everything.

What was once the domain of Renaissance artists and cognitive psychologists is now an essential part of the modern designer’s toolkit. Whether crafting a skyscraper that inspires awe or a mobile app that is a joy to use, the goal is the same: to create a space that is intuitive, understandable, and works in harmony with how our brains are naturally wired to see the world. By mastering this unseen language of space, we can build a world, both physical and digital, that is not just more functional, but also more beautiful and more human. The future of design depends on our ability to honor the deep-seated needs of our spatial awareness.