Have you ever felt a sense of profound unease in the faint, sterile glow of a screen, a quiet but persistent feeling that despite our boundless digital connectivity, some essential connection has been lost? This subtle malaise is not an anomaly of modern life; it is the accumulated echo of a multi-millennia-long story. This analysis posits that the human-nature relationship is not a static backdrop to history but a dynamic system that has evolved through distinct and consequential phases.

It is a trajectory that begins with humanity’s symbiotic integration within ecosystems, shifts to a paradigm of management and control during the agricultural revolution, and accelerates toward domination during the industrial age, culminating in our current state of critical reflection within the Anthropocene.

Understanding this historical arc is not merely an academic exercise. It is a foundational prerequisite for designing healthier future systems, both physical and digital. Throughout these epochal shifts, one constant variable has remained: an innate human need to affiliate with nature, a concept now identified as the biophilia hypothesis.2 The following overview will trace the history of our interactions with the natural world to diagnose the origins of our contemporary disconnect and establish a data-driven basis for a necessary, conscious re-integration.

Table of Contents

The Paleolithic Paradigm: Humanity as an Integrated System within Nature

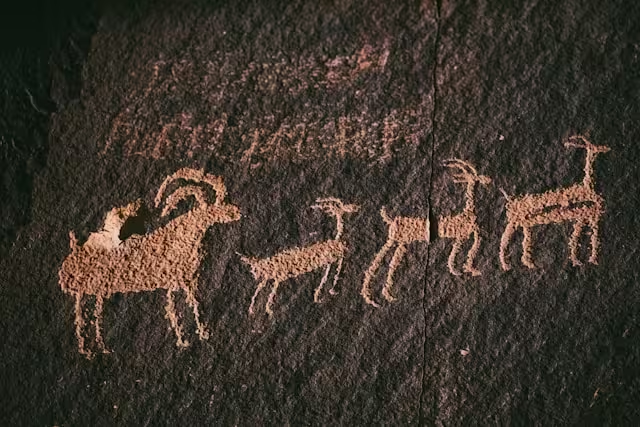

For over 95% of human history, our species functioned not as an external force acting upon nature, but as a fully integrated component within it. The Paleolithic paradigm was one of symbiosis, governed by deep, empirical observation now recognized as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Hunter-gatherer societies possessed a granular understanding of flora, fauna, and seasonal cycles that was essential for survival. This relationship was not purely utilitarian; it was codified in animistic belief systems where natural elements, animals, and landscapes possessed agency and spirit, a worldview evidenced in the sophisticated iconography of sites like the Chauvet Cave.

The human ecological footprint was intrinsically limited by nomadism and low population densities. While early humans did alter their environments through practices like controlled burning, these actions were localized and often enhanced biodiversity, functioning within the existing ecological parameters rather than overwhelming them. This era represents the baseline for the human-nature dynamic: a state of profound, functional immersion.

The Neolithic Revolution: The First Great Decoupling

The agricultural revolution, beginning approximately 12,000 years ago in regions like the Fertile Crescent, represents the first fundamental decoupling of humanity from wild, self-regulating ecosystems. The domestication of plants and animals was a radical assertion of control, transforming humanity from foragers into active environmental managers. This shift necessitated sedentary living, which in turn enabled population growth and the development of complex settlements like Çatalhöyük. With this came the novel concept of land ownership and the first large-scale, deliberate environmental modification: forests were cleared for fields, rivers were diverted for irrigation, and select species were propagated at the expense of others.

In response to the query of when humans began to “destroy” nature, the Neolithic period marks the inflection point where human impact transitioned from localized and transient to permanent and systemic, establishing a trajectory of resource management and environmental engineering that would define all subsequent civilizations.

Ancient Civilizations: Codifying Nature as Resource and Symbol

As civilizations emerged from the Neolithic shift, their intellectual and material expansion necessitated a more formalized relationship with the natural world, which manifested in three distinct modes. The Greek philosophical tradition, exemplified by Aristotle and his student Theophrastus, approached nature as a rational system to be understood through observation and categorization—a logos to be discovered.

In contrast, the Roman Empire operationalized nature as a set of resources to be engineered for imperial ambition; the construction of aqueducts, roads, and extensive mining operations demonstrates a worldview of nature as a force to be tamed and exploited for human utility. This is meticulously documented in works such as Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis.

A third mode, prominent in civilizations like ancient Egypt, integrated nature into the divine, where forces like the sun (Ra) and the Nile River were deified, creating a relationship of reverence that coexisted with the pragmatic necessity of agricultural harnessing. In each case, nature was no longer a system one lived within, but an external entity to be studied, managed, or worshipped.

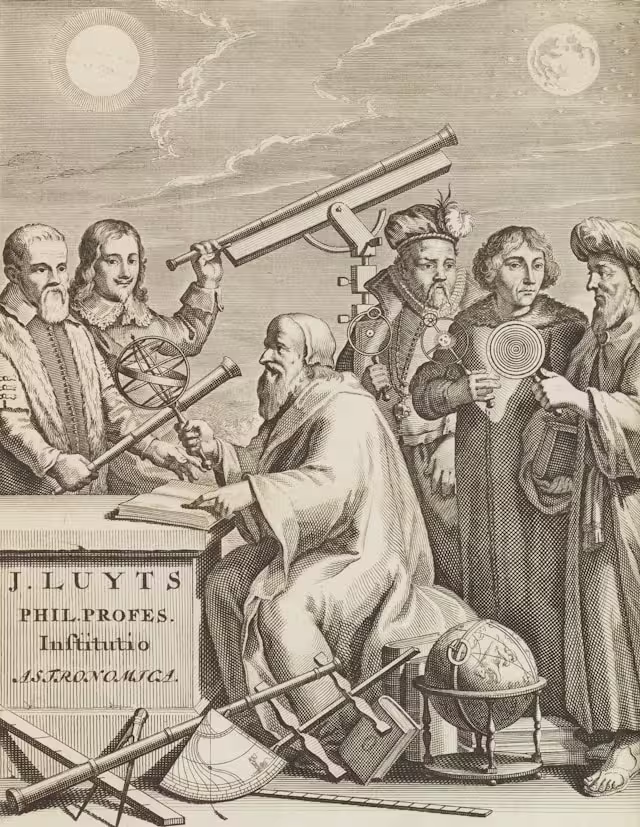

The Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution: Nature as Mechanism

The period of the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution precipitated the most profound philosophical shift in the human-nature relationship since the advent of agriculture. Building on the work of thinkers like Francis Bacon, who advocated for the use of science to exert dominion over nature for human benefit, this era systematically disenchanted the natural world.

The most critical development was the “Cartesian Divide,” a concept from René Descartes that rigorously separated the thinking mind (res cogitans) from the mechanical, material world (res extensa). This dualism effectively rendered nature a complex but inanimate machine, devoid of spirit or agency and governed by predictable, mathematical laws. Nature was no longer a living entity with which to have a relationship, but an object to be disassembled, analyzed, and ultimately, controlled. This mechanistic worldview provided the essential philosophical license for the unprecedented resource exploitation that would follow.

The Counter-Currents: Romanticism and Transcendentalism

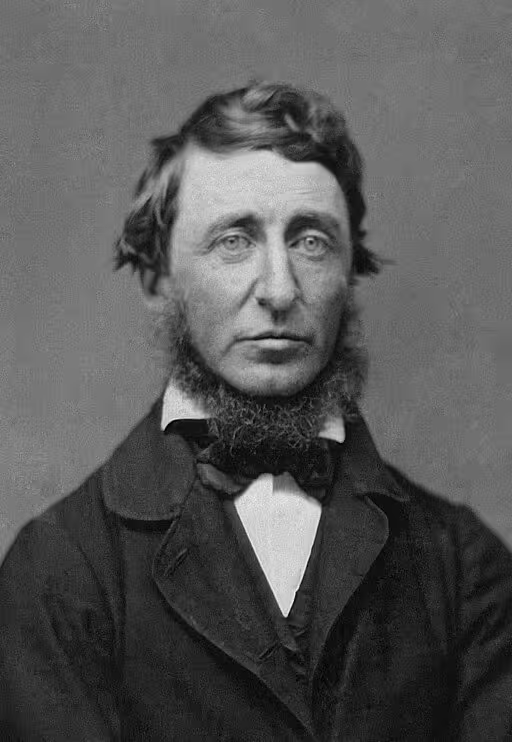

As a direct psychological reaction to the mechanistic worldview and the encroaching grime of the Industrial Revolution, the late 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of powerful counter-movements. Romanticism, particularly in the works of artists like J.M.W. Turner and poets like William Wordsworth, rejected the cold rationalism of the Enlightenment. It championed emotion and intuition, finding in nature a source of the sublime—an experience of awe and terror before untamed, powerful landscapes that transcended human understanding.

In the United States, this evolved into Transcendentalism, a philosophy advanced by figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Through his experiment at Walden Pond, Thoreau argued that direct immersion in nature was a corrective to the corrupting influences of society and a path to spiritual and intellectual truth. This movement, later influencing preservationists like John Muir, did not see nature as a machine or a resource, but as a sanctuary and the very source of humanity’s moral and spiritual character.

The Industrial Revolution and The Great Acceleration: Nature as Fuel

The Industrial Revolution and the subsequent “Great Acceleration” of the mid-20th century represent a phase change in the scale and velocity of human impact on the planet. Driven by the energy density of fossil fuels, this era treated the entirety of the natural world as a standing reserve of fuel and raw materials for a global industrial engine. This period triggered an exponential increase in resource consumption, pollution, and population growth, driving a mass urbanization that fractured the everyday connection to nature for a majority of humanity.

The visible consequences of this unchecked exploitation—deforestation, species extinction, and widespread pollution—gave rise to the modern environmental movements. A critical distinction emerged between conservation, championed by figures like Gifford Pinchot and President Theodore Roosevelt, who advocated for the wise, efficient use of natural resources, and preservation, advocated by John Muir, who fought to protect wilderness areas like Yellowstone National Park from any human exploitation whatsoever.

The Anthropocene and the Digital Age: A New Synthesis?

We now operate within the Anthropocene, a proposed geological epoch defined by the fact that human activity is the primary driver of change in planetary systems. This era presents a fundamental paradox: through digital technology, we have unprecedented access to information about the global environment, yet we are more physically and psychologically detached from it than ever.

The groundwork for our current awareness was laid by seminal 20th-century thinkers. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring exposed the systemic dangers of pesticides, awakening the public to the interconnectedness of ecosystems. Aldo Leopold, in A Sand County Almanac, proposed a “Land Ethic,” extending moral consideration to the entire biotic community.

This line of thought culminates in the work of Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson, who formulated the Biophilia Hypothesis. Wilson proposed that humans possess an innate, genetically determined urge to affiliate with other forms of life. This hypothesis provides a scientific framework for the intuitive feelings expressed by the Romantics and Transcendentalists, and it explains the modern malaise felt amidst sterile, nature-divorced environments. It argues that our need for nature is not a preference but a biological necessity, making its absence in our modern lives a critical design flaw.

Conclusion: Learning from the System’s History to Design the Future

The historical trajectory of the human-nature relationship is one of progressive alienation—from integration to management, to objectification, and finally to the profound disconnect of the digital age. This is not a terminal diagnosis. It is a data set that mandates a new approach. The evidence presented confirms that our biological selves have not kept pace with our technological evolution; the innate need for nature identified by the Biophilia Hypothesis persists.

A sustainable, functional, and psychologically healthy future therefore requires a conscious and deliberate re-integration of nature into our built world. This extends beyond parks and conservation to the very fabric of our lives: our architecture, our communities, and critically, our digital interfaces. By understanding the history of how this connection was fractured, we can leverage fields like Biophilic Design to systematically and effectively restore it.